The first edition of the Kalevala appeared in 1835, edited by Elias Lönnrot based on the popular epics he had collected in Finland and Karelia.

When the Kalevala first appeared in print, Finland had been an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia for a quarter of a century. Before this, until 1809, Finland was part of the Swedish empire.

The Kalevala marked an important turning point, brought a small unknown people to the attention of other Europeans and strengthened Finns’ self-confidence and faith in the possibilities of the Finnish language and culture. The Kalevala began to be called the Finnish national epic.

Meanwhile Elias Lönnrot continued to collect other popular poems and new material quickly accumulated. Using this new material, Lönnrot published a second expanded version of the Kalevala in 1849.(1)

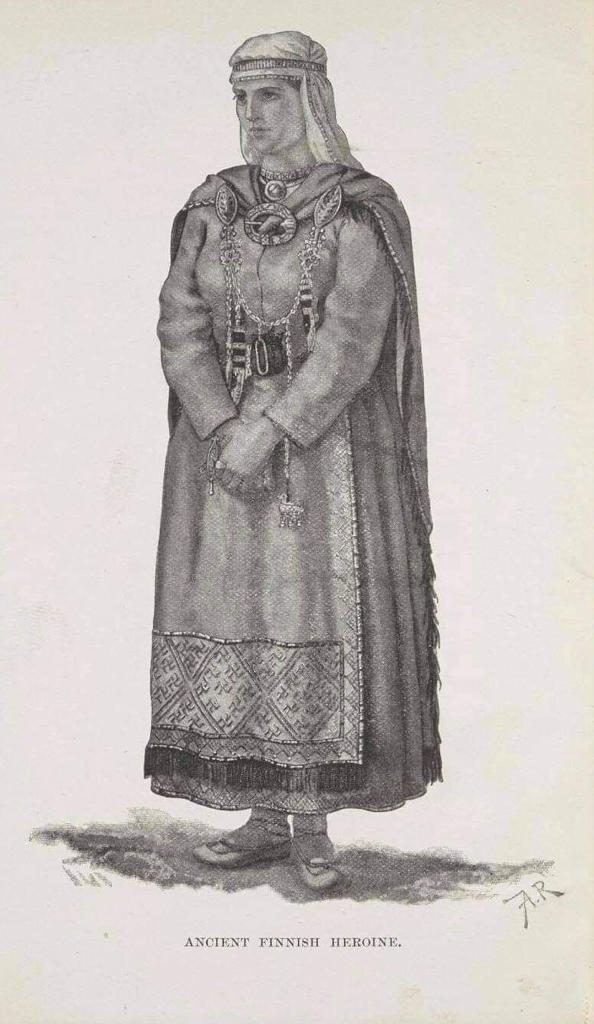

In our volumes we have given ample space to Finnish mythology, which we consider the basis of the Vanic cult. This mythology has many features shared with Finnish Estonian mythology and its non-Finnish neighbors, the Baltics and Scandinavians.

Some of their myths are even distantly related to the myths of other Finno-Ugric speakers such as the Sami.

Traditionally the Sami lived in a community of families called Siida, whose members collaborated with hunting and fishing. Officially the number of Sami is estimated between 44,000 and 50,000 people. It is assumed that around 30,000-35,000 live in Norway, 10,000 in Sweden, 3,000-4,000 in Finland and 1,000-2,000 in Russia. However, some think the actual number is considerably higher. The Sami have a Finno-Ugric language which is most closely related to Finnish, Estonian, Livonian, Votic and several other little-known languages.

Altogether there are fifty dialects, but these fall into three main groups (east, center and south) which are incomprehensible to each other. The Northern Sami dialect is the most widespread. Other dialects are Lule Sámi, Kildin Sámi, Inari Sámi, Skolt Sámi, Southern Sámi, Ter Sámi, Ume Sámi and Pite Sámi. Traditionally the Sami believed that specific spirits are associated with certain places and with the dead. Many are their myths and legends regarding religious practices, not to mention the constant presence in the literature of the legendary figures of the Trolls. (2)

Finnish mythology survived within an oral tradition of mythical songs of poetry and folklore until the 19th century.

Despite the gradual influence of the surrounding cultures the father god “Ukko” was originally born only as a spirit of nature like everyone else. All this unites with the religious conception of the Vanic people in the evolutionary stages of the concepts of natural spirit which evolves into daimon then deity, divinity to return through folk as a devil with the advent of Christianity.

Among the animals, the most sacred was the bear, whose real name was never spoken aloud, for fear that its species was advancing and interfering with the hunt.

The bear “karhu” in Finnish, was seen as the incarnation of ancestors and for this reason was called with many euphemisms: “Mesikämmen”, “otso”, “kontio” and “lakkapoika”

Cristfried Ganander’s Mythologia Fennica, published in 1789, was the first real academic foray into Finnish mythology.

Research on Finnish folklore intensified in the 19th century. Scholars such as Elias Lönnrot, JF Cajan, MA Castrén and DED Europaeus have traveled around Finland transcribing popular sung poems.

From this material Lönnrot modified the Kalevala and the Kanteletar.

The Finnish people believed that the world was formed by the explosion of a waterfowl egg. It was believed that the sky was the top cover of the egg, alternatively it was seen as a tent, which was supported by a column at the north pole, under the pole star.

It has been explained that the movement of the stars is caused by the rotation of the celestial dome around the North Star and itself. A large vortex was caused at the north pole by the rotation of the sky column. Through this vortex the souls could go out of the world to the land of the dead, Tuonela.

It was a home or an underground city for all the dead, not just the good or the bad. It was a dark and lifeless place, where everyone slept forever. The shaman could go to Tuonela in a trance to ask for guidance from the ancestors. Cross the river of Tuonela’s death. If he had a valid reason, a boat would come to get him.

At the ends of the earth was Lintukoto, “the house of the birds”, a warm region where birds lived during the winter. The Milky Way is called Linnunrata, “the path of the birds”, because it was believed that birds moved along it to Lintukoto and back.(3)

The poem we are examining today has inspired many artists. Tolkien first discovered Kalevala’s tale when he was a schoolboy in Birmingham.

Arriving at Oxford University a year later, Tolkien began writing his own version of the Finnish myth. But after a few months he suddenly gave up. The manuscript is about 26 pages long and breaks off in the middle of a sentence.

The Kalevala is written in non-rhyming trochei and octosyllabic dactyls (the Kalevala meter) and its style is characterized by very parallel alliterations and various repetitions.

Let’s say that all the traditional Finnish poetry was written in a single meter: the runo.

From Old Norse rýna «to make secret speeches», German raunen «to whisper».

Hence the link with the magic verb, a word that enchants a magical character.

The singer was the laulaja who was also runoja, because he transmits and creates tradition, he was runoseppä poet, runoniekka master of runo.

Poetry is much revered and even more so are the words, sanat (plural of sana), endowed with great divine power and efficacy. The plural sanat is used to indicate both the poem and the magic song (fi. Loitsuruno) which is the basis of the runo, originally created for magical purposes and then passed to indicate any type of poem.

The oldest term that distinguishes Finnish folk poetry is runo. It is used to designate traditional songs or poems with a unique form, fixed by the fathers at the time when the Finns were pagans, to express their religious conception. Of spontaneous, simple and primitive origin, the runo has its roots in the nature and phonetic peculiarities of Finnish. The harmony between vowels and consonants is heightened by the rhyme (fi. Loppusointu) and alliteration (fi. Alkusointu), the latter of fundamental importance for the “Kalevalian” verse. (3)

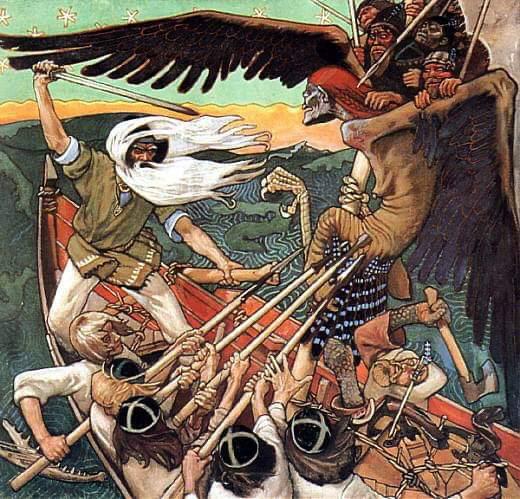

This poem inspired many outstanding works of art, for example the paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kallela and the musical compositions by Jean Sibelius. The epic style and meter of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem The Song of Hiawatha also reflect the influence of the Kalevala. (4)

The Kalevala, 32 cantos, 1835; enlarged in 50 cantos, 1849, it is the home of the main characters of the poem, it is a poetic name for Finland, which means “land of heroes”.

The leader of the “sons of Kaleva” is the old and wise Väinämöinen, a seer with supernatural origins, who is a master of the kantele, the Finnish harp stringed instrument.

Other characters are the skilled blacksmith llmarinen, who forged with others the “lids of the sky” when the world was created, he had a good relationship with Väinämöinen and respected him. The two traveled often. It was he who built the Sampo for Pohja and married Louhi’s daughter. He was brave and honest.

Lemminkäinen, the carefree warrior who charms women;

Louhi, the ruler of Pohjola, mighty land to the north; and the tragic hero Kullervo, who is forced by fate to be a slave from childhood.

Among the main plays of the poem are the creation of the world and the adventurous journeys of Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen to Pohjola to woo Louhi’s beautiful daughter.

The Kalevala begins with the traditional Finnish creation myth, which leads to the creation stories of the earth, plants, creatures and the sky. Combat and internal storytelling are often accomplished by the character or characters involved chanting their exploits or wishes.

Many parts of the stories involve a character who approximates or requires texts (spells) to acquire some skills, such as boat building or mastery in iron making.

Sampo is a cornerstone of the whole work. Many actions and their consequences are caused by Sampo itself or by a character’s interaction with Sampo.

Its nature is still being studied, it is identified with a talisman that gives well-being to those who own it.

I do not resume the parts because it deserves to be read in its entirety, the division of the poem is the following.

Runo 1-2. Creation of the world.

Runo 3-10. First cycle of Väinämöinen.

Runo 11-15. First Lemminkäinen cycle.

Runo 16-18. Second cycle of Väinämöinen.

Runo 19-25. First cycle of Ilmarinen (the wedding).

Runo 26-30. Second cycle of Lemminkäinen.

Runo 31-35. Kullervo cycle.

Runo 39-44. The theft of the sampo.

Runo 45-49. Louhi’s Revenge.

Runo 50. History of Marjatta.

Although the Kalevala depicts the conditions and ideas of the pre-Christian period, the last chant seems to predict the decline of paganism: the servant Marjatta gives birth to a son after ingesting red myrtle. Väinämöinen orders the boy to be killed, but the boy starts talking and reproaches Väinämöinen for misjudging. The child is then baptized king of Karelia. Väinämöinen sails leaving only his songs and his kanteles to the Finnish people.

The poem ends and the singers say goodbye and thank their audience.

Notes:

1 Anneli Asplund e Sirkka-Liisa Mettomäki, ottobre 2000, in https://finland.fi/arts-culture/

2 Laugrith Heid, La stregoneria dei Vani, Anaelsas Edizioni

3 Virtanen, Leea and Dubois, Thomas. (2000). Finnish Folklore

4 E. Zanchetta, Comparison between the Germanic and Finnish conception of the afterlife

Photo: Akseli Gallen-Kallela

_____

*Shares without reference to the source are subject to complaint, since the elements of copyright established by italian law are infringed*

Vanatrú Italia

Il gruppo dei traduttori composto da Federico Pizzileo, Irene Parmeggiani, Valentina Moracci, Elio Antenucci, Federico Montemarano, Silvia Giannotti e Sonia Francesconi si occupa della traduzione in più lingue degli articoli e del sito web.