A study of the cognitive and spiritual dimensions of pre-Christian Scandinavian falconry.

This article aims at a first study with relative, given the scarcity for the present of information, hypotheses, on the falconry reality.

It is possible to assume that the hawks were well known in the northern countries as early as the sixth century, thanks to the movements of peoples from the east, the question arises as to whether there were aspects of the art of falconry, not known in other kingdoms during this period.

Already formed around 500 AD and evolved up to the era of Viking raids, falconry in the peoples of the north has exclusive peculiarities in the relationship between the falconer and the falcon; this given by the unequivocal presence in Nordic animal art – as well as in Myths – of interactions between birds with Witches and Shamans.

Falconry is therefore reinterpreted in the human-animal relationship typical, as well as hereditary, of Scandinavia; analyzing that the relationship between a falconer and his falcon could very well have, as is also found with animals such as wolves and bears in the Myths, a shamanic implication linked to changes in shape suitable for magical purposes.

The debate on “when” and “by whom” falconry was introduced in Scandinavia has been going on for more than a century and a half, and at present the best general guide on the history of ancient falconry is recognized by scholars to be the work by Hans J. Epstein. In fact, he was the first to agglomerate and analyze historical documents related to falconry, coming from different Eurasian and European civilizations.

According to Epstein, falconry is in fact not a Germanic invention; rather a technique developed in the near Middle or Far East, introduced in Europe during the migratory period by one or more tribes of the time: Alani (Sarmatians) – Vandals – Huns.

Thesis, however, also confirmed by another scholar: Claus Dobiat.

Other historical and artistic scholars support the possible entry of falconry in Scandinavia, through commercial relations with Franks and Frisians, including England.

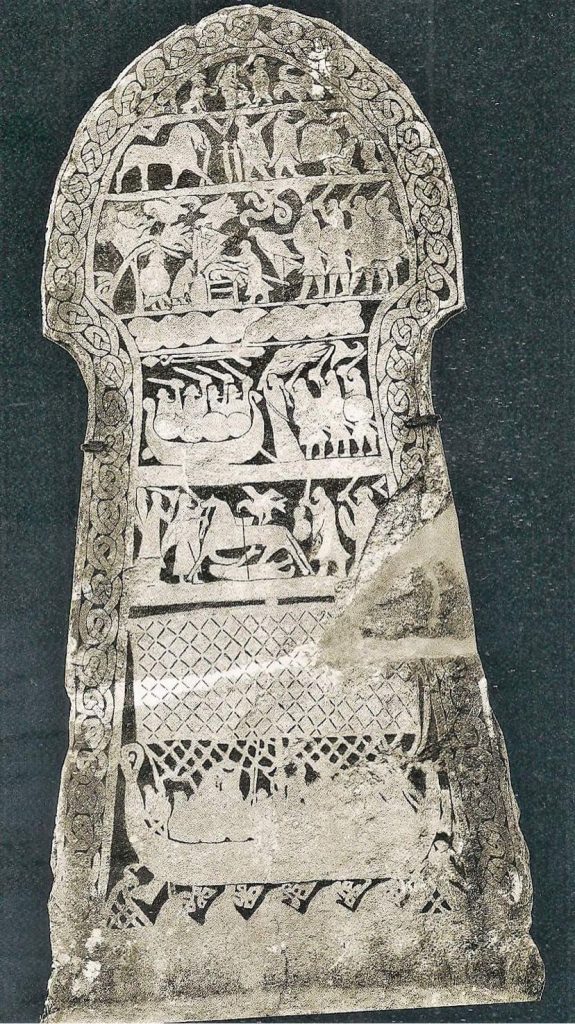

The issue is still widely debated today; currently the only certain information is that the first distinguishable sign of falconry in Scandinavia is of Swedish origin. Gotland, specifically.

In the history of this practice, three purposes have always stood out:

- the search for meat for survival

- a search for profit given by the meat trade

- a manifestation of power given by the elite practice itself.

But in pre-Christian Scandinavia, even with very little evidence that allows only hypotheses for the moment, we cannot exclude that in addition to the three mentioned above there was a fourth purpose: the spiritual / shamanic one.

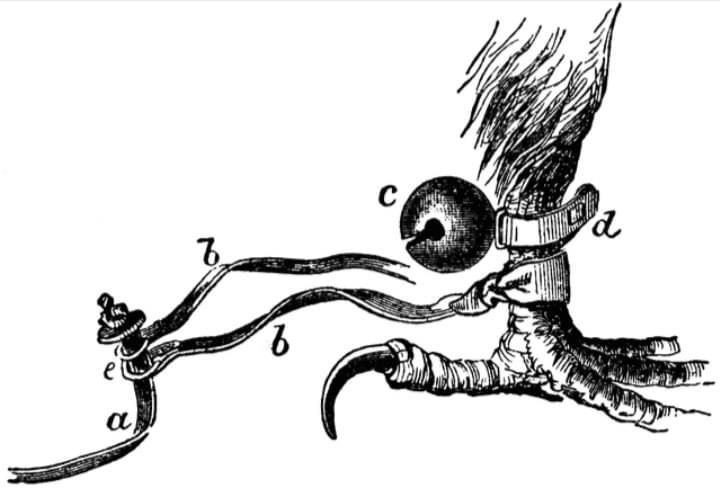

This leads us to interesting information related to the use of certain bells, used in daily life both in Finland and Scandinavia, as protection from the dangers of the outside world at the safe borders of the villages.

It is believed that these bells were also used in the falconry art for various reasons; the main ones were: differentiating a trained hawk from a wild one, and creating a soundscape indicative of human activity. Concepts easily transferable to the context of falconry.

The bell ideally establishes the boundary between domestication and nature – between Midgard and Utgardr – and as long as the falcon, as a fully trained bird of prey carries its bell, it is protected by the wilderness.

Figurative representations linked to the falconry context of pre-Christian Scandinavia are unfortunately still quite rare; considering, however, the relationship between man and beast present in the esoteric tradition of the north, we can assume (also taking a cue from myths), that there were also practices of change of shape linked to the hawk.

Mircea Eliade himself explained that both warriors and shamans (and witches, we add), through certain practices, they transformed themselves into the animals they chose; and this process led them to obtain abilities previously unthinkable for a human being.

For example, Dei Berserkir and Ulfhednar are said to have felt no fire or iron wounds in ecstasy.

Or Snorri tells us about Odin, saying:

“His body lies as if he were sleeping or dead, while he becomes a bird or a beast, or a dragon and in an instant he takes himself to faraway countries …”

We, thanks to the text “The Witchcraft of the Vani” know even more:

<< A seidkona is described, which changes appearance from lion to dragon, an element that is precisely in the conception of the practice of this Sorcery; works with both higher and lower levels of the sub-unconscious … The animal part already resides in man and is hidden, except when it is evoked to provide exceptional skills and service to the Witch in honor of the deities invoked. >>

Thanks then to the countless studies on symbolic representations and sagas, linked to the change of form attributable to Berserkir and Ulfhednar, it can also be deduced that this also included birds.

This thesis is plausible in light of two factors:

The first is that on some brooches with representations of birds the presence of a human head was noted between the wing tip and the bird’s head.

In a traditional shamanic context, falconry could therefore be seen as a possible form of seidr; especially if also analyzed according to the conception present in the Myths of Odin’s two ravens, whose names are very significant: Mind – Memory.

Expressions related to Wisdom and Intelligence.

The second is given by what the texts teach about the Valkyries and their feather robes, and about the main Vanica Goddess: Freya Vanadis, Master of all kinds of witchcraft and owner of a robe of … falcon feathers.

Plausibly such feathered robes were worn by shamans during shamanic travel ceremonies in the 9 Worlds, and also during divination practices.

All the elements described therein indicate, in the transformation into a bird, a very frequent element in the Nordic religious universe; not only connected to Odin but also to female deities more vanic.

1. Laugrith Heid, La Stregoneria dei Vani, Anaelsas edizioni.

2. Mircea Eliade, Lo Sciamanesimo e le Tecniche dell’Estasi.

3. Ármann Jakobsson og Sarah Croix, Leiðbeinandi.

4. Hans J. Epstein, The Origin and Early History of Falconry.

5.Claus Dobiat, Early falconry in central Europe on the basis of grave finds, with a discussion of the origin of falconry.

6. Enciclopedia William & Robert Chambers – A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People (Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott & Co., 1881)

Vanatrú Italia

Il gruppo dei traduttori composto da Federico Pizzileo, Irene Parmeggiani, Valentina Moracci, Elio Antenucci, Federico Montemarano, Silvia Giannotti e Sonia Francesconi si occupa della traduzione in più lingue degli articoli e del sito web.