The figure of the dragon has always been an object of fascination in the minds of the European and Eurasian people.

During the thirteenth century, in Iceland, this symbol consisted not only of a purely imaginative vision of man, but of a real creature that contained pure knowledge.

It can be seen in the analysis of sagas such as Þiðreks saga af Bern and Þáttr af Ragnars sonum, in which the intent of literary use of this figure prevails considerably, much more than other more nebulous texts such as the Brennu-Njáls saga.

But the image of the dragon dates back to a long time ago. In classical times, Homer mentions him as a serpentoid animal with legs and wings, characterized by acute eyesight, as strong as a lion and agile as an eagle. He is not the only author to talk about it, because a dragon watches over the famous Golden Fleece, mentioned in the famous Argonautics of Apollonio Rodio, or when he spoke of Heracles and the dragon Ladone, whose body was placed in the sky, as Constellation of the Dragon.

Over the centuries, hundreds of myths and stories that revolve around this figure have come to us from all over Europe and Euro-Asia. In any case, of fundamental importance when it comes to analyzing motifs and elements belonging to our religion, is also to study the origin of the terms in depth.

These creatures – dragons – were originally identified in Old Norse with the terms “ormr” and “linnormr”, ie with names borrowed from the Latin draco, which in turn derives from the Greek δράκων. However, what is really interesting to note is the first attestation of the latter word, which dates back to Homer’s Iliad, as a declination of δέρκομαι, that is “to see clearly”.

The assumption of this term as something related to a snake is therefore very interesting and above all significant.

In fact, Evans (1) underlines the natural connection due to the vision of this creature as a guardian of the limit, as a creature that offers the possibility of being able to get a glimpse beyond the threshold and that somehow surrounds the entire destiny of the cosmos.

Like Niðhǫggr in the skies and Jörmunngandr at the roots of Yggdrasill, so also in other cosmologies we find the archetype from which everything becomes, as Zimmer’s analysis suggests in relation to Shesha: “ It is a figure that represents the remnant that remained after the earth, the upper and infernal regions, and all their beings, were molded and drawn from the cosmic waters of the abyss. “(2)

In the analysis of these two elements of our mythology, it somehow reconnects to a latent and serpentoidal energy that surrounds the entire Universe and that yearns for an evolution; a revolution that inevitably passes from a reabsorption of the Cosmos in the primordial uterus, in the primary matrix of existence. In this necessary formula we find on the one hand Jörmungandr biting his tail and preventing the cosmic ocean from flooding the world, on the other Niðhǫggr chewing the roots and ultimately carrying the bodies of the dead among his feathers. The skilful balance that is maintained between the two allows the manifestation on the level of earthly existence.

The energy that is released and that refers to the serpentoidal figures is materially perceptible even if not visible, eternal and at the same time finite, belonging to a unique space-time dimension, which also emanates from our soul sphere: the daimon.

Also for these reasons the witch appears as an ambiguous, liminal being, in continuous communication with the heavens and the underworld, starting from the way she speaks, which almost always appears ambiguous. Intentionally ambiguous, precisely because ambiguity allows for the integration of the two and multiple aspects of existence, on all possible levels.

In this regard, I recommend reading our article.

It is significant that the personal name Orm (snake), as in Gunnlaug Serpent-tongue and Orm Barreyiarskjald, is connected to the act of the verb. As far as the evidence can support it then, Óðinn, apart from the real snakes, is the only individual to receive these names, and curiously these names are the same as two snakes that inhabit with Niðhǫggr. ” (3).

Another natural element of the snake is its venom. It undoubtedly represents that terrifying part, connected to Nástrǫnd, in the kingdom of Hel, described thus: “ Sal sá hon standa sólo fiarri Nástrǫndo á, norðr horfa dyrr; fello eitrdropar inn um lióra, sá er undinn salr orma hryggiom ”.

These particular, unique and liminal attributes cause the snake to become a symbol of initiation.

We know well how metaphors can help to create a new way of understanding the world, of revealing the arcana and hiding the secrets, so initially the iconography of the snake was mainly imprinted in objects and accessories to wear, as is found in bracts , although they are not the only standouts.

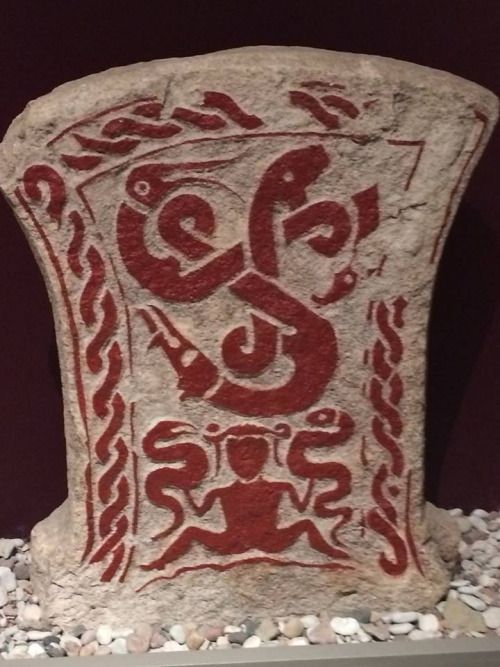

In fact, it is possible to see it again in stones such as Ormhäxan (pictured), a famous stone that tells more than one might think. Here the figure of a witch appears accompanied by beasts such as the snake and the bird, which together represent the idea of the threshold, a fundamental element for initiation, while above a solar-like symbol offers the evolutionary incipit.

The dragon represents a new beginning, because it is an integral part of a Chaos that generates knowledge, and the one who is initiated and goes through the trials of the Dragon, is reborn to new life, as a new individual, himself but different (4).

Dérkomai could represent the level of awareness and management of one’s primordial instincts, represented by this figure. Introspection that leads to “seeing clearly” the manifest and the unmanifest.

The eye of the Dragon is the gash in the Primordial Void, which allows you to get to know the Truth, dissolving the chains and illusions of the human being, experiencing the absolute and double principle of which the essence is made, therefore a ” see clearly ”.

1) Evans, Jonathan. “’As Rare As They Are Dire’: Old Norse Dragons, Beowulf, and the Deutsche Mythologie.” The Shadow-Walkers: Jacob Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous. Edit. Tom Shippey. MRTS, Tempe, AZ:2005.

2) H. Zimmer, Miti e simboli dell’India, Adelphi, Milano 2012

3) Hedeager, Lotte. Iron age myth and materiality: an archaeology of Scandinavia. Routledge, New York: 2011.

4) De Vries, Jan. Heroic Song and Heroic Legend. Trans. B.J. Timmer. Oxford University Press, London: 1959

*Shares without citing the source are a cause of action because they infringe the elements of copyright enshrined in Italian law*

Federico Pizzileo

Seminarista e docente presso l'Accademia Vanatrú Italia.

Gli studi di linguistica e di filologia germanica universitari gli hanno aperto il mondo verso uno sguardo nuovo alle parole e alle radici europee. Con l'arrivo in A.V.I. ha potuto scoprire la sua origine pagana, entrare nella stregoneria, nell'esoterismo e nell'occultismo e acquisire il metodo di ricerca innovativo.

Oggi, oltre a essere seminarista, si occupa anche della sezione di classi relativa al mito, al rito, alle saghe e al recupero del pensiero dell'uomo antico.